Missing Persons

November 11, 2015–March 21, 2016

Stanford, California—The Cantor Arts Center presents a new exhibition, Missing Persons, which considers both the aesthetic and political implications of what it means to be missing. The 50 photographs, prints, artist books and archival objects on view visually play with the tension between absence and presence, so that the absence of the subject becomes the substance of the work. The exhibition features objects that range from a 19th-century silhouette by American painter Raphaelle Peale to contemporary works by internationally known artists including Kara Walker, the Guerrilla Girls, Lee Friedlander, Richard Misrach, Allen Ruppersberg, Diane Arbus, Ana Mendieta, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Glenn Ligon, Sophie Calle, Catherine Wagner and Ester Hernandez. Many of these artists recognize populations who are excluded from representation, or who have gone missing under oppressive political institutions; art works address those displaced from their homes by colonialism, gentrification, incarceration and authoritarian regimes.

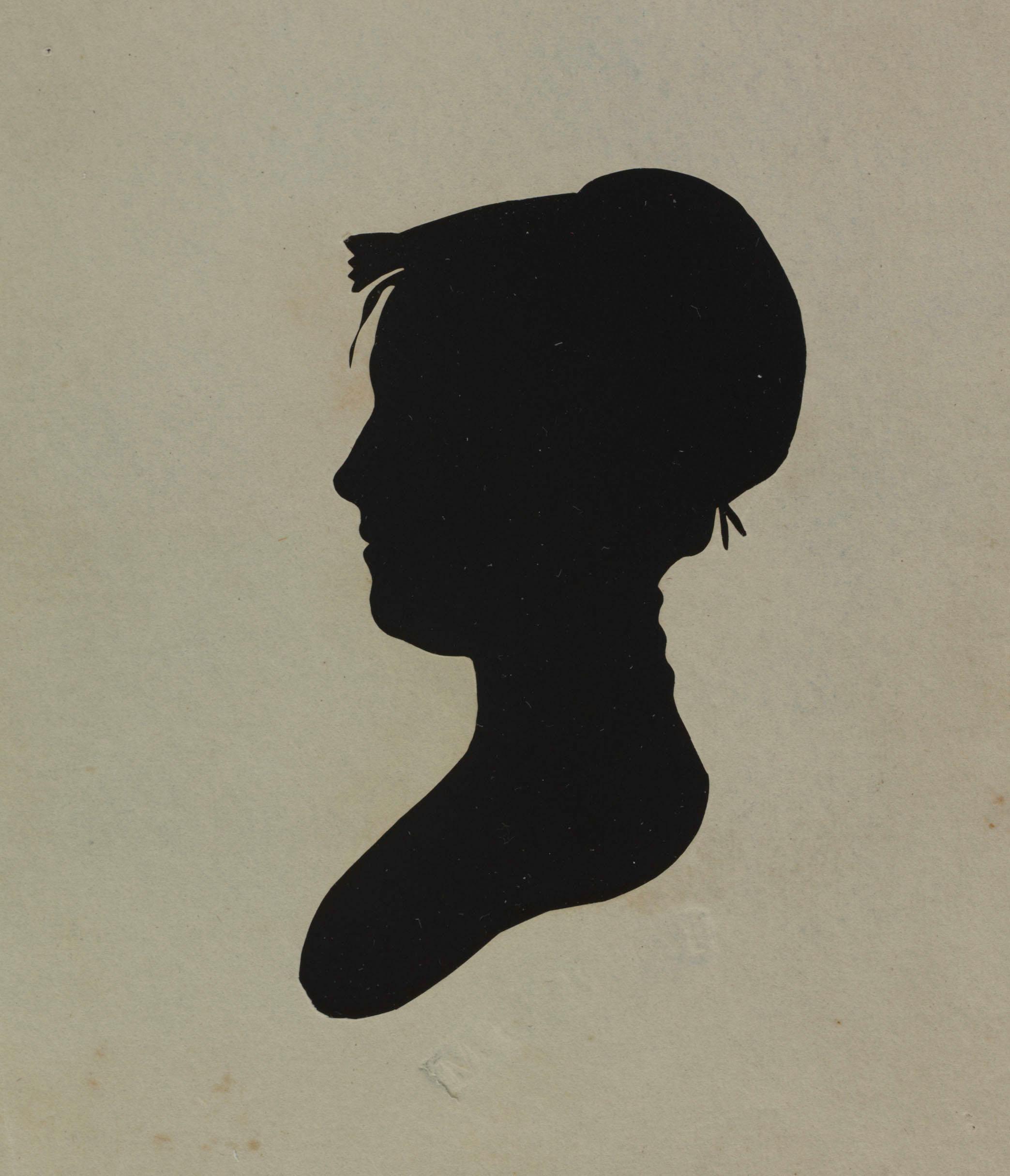

Missing Persons begins with an introductory section featuring both contemporary and historic artworks. The first work visitors encounter, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) by artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, is a 175-pound pile of multi-colored hard candies that represents the body of Gonzalez-Torres’s partner, who died from AIDS-related complications in 1991. Visitors are encouraged to consume a single piece of candy from the pile. As the pile diminishes, it gradually echoes the deterioration of Ross’s body and memorializes his life. The introductory section continues with a selection of 19th-century silhouettes and highlights artists who use shadow and tracing to depict a human presence. Included in this section is Portrait of H. L. (c. 1820), a miniature silhouette made in Charles Willson Peale’s American Museum in Philadelphia. This “shadow portrait,” produced by tracing the projected silhouette of the sitter, was a popular form of portraiture in the 18th and 19th centuries before the advent of photography. And yet the resulting profile speaks more to absence than presence: all that remains is a traced shadow, standing in for the body of a person who is no longer with us.

Following this introductory section, the exhibition is divided into three sections: “Wanted,” “Remains” and “Unseen.” In “Wanted,” artists consider systemic injustice—from slavery to mass incarceration, gentrification and political violence. The word “wanted” takes on multiple meanings in this section; the artists might “want” justice, freedom from oppression, or representation on the walls of museums and in the pages of history. Historical objects such as a 19th-century runaway slave advertisement and the F.B.I. wanted poster for Angela Davis ask the viewer to think about those who intentionally flee from a system of enslavement, imprisonment or institutional racism. Contemporary artists Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker provide a modern-day lens on the legacy of slavery in America.

“Remains” focuses on the repercussions of invisibility, and the objects that make visible those people or communities excluded from the historical record. Photographs by Richard Barnes and Sophie Calle direct our gaze downward, documenting the people and places outside of our everyday field of vision. Meanwhile objects from the Stanford family’s personal collection tell a complex story of family legacy: a missing lock of hair conjures the memory of the Stanfords themselves, while a Native American cradle bought by Jane Stanford in 1899 directs our attention to indigenous peoples displaced by white settlement and industry.

The works in “Unseen” highlight the artistic processes of framing and composition, and also ask visitors to consider how the unseen or off-frame can assert their presence. The hands of Judy Dater, the bare, tattooed chest by John Gutmann and the eyeball on television by Lee Friedlander present fragmented bodies, prompting the viewer to imagine the parts of the image that they cannot see. Like photographs, objects can be informed by the invisible and unseen: the shoes that Allen Ginsberg wore while trekking through Czechoslovakia in 1965 serve to memorialize the body and words of the legendary Beat poet.

This exhibition is curated by five graduate students at Stanford University: Ph.D. candidates in Art History Caroline Murray Culp, Alexis Bard Johnson, Natalie Pellolio and Yinshi Lerman-Tan; and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Theater and Performance Studies Gigi Otálvaro-Hormillosa. It is the culmination of a graduate seminar about curatorial practice co-taught by Connie Wolf, the Cantor’s John and Jill Freidenrich Director, and Richard Meyer, Robert and Ruth Halperin Professor in Art History. The class spanned three academic quarters, totaling about seven months from the initial meeting of the curatorial team to the final exhibition and publication. The student curators were given only one real parameter for the exhibition: that it be drawn primarily from the permanent collection at the Cantor Arts Center and from other Stanford University Special Collections. After researching, proposing and rejecting a host of ideas, the students eventually selected Missing Persons as the exhibition’s title and concept. Throughout the spring and summer quarters, the group grappled with questions about scope, concept and installation, and also wrote text for the exhibition labels and publication. Working closely with Wolf and Meyer, the students read and discussed histories and theories of curatorial practice and carefully researched each artist and object in the exhibition.

This exhibition is supported by a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation designed to enhance the training of Ph.D. students in Stanford’s Department of Art & Art History.

Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University

Founded when the university opened in 1891, the museum was expanded and renamed in 1999 for lead donors Iris and B. Gerald Cantor. The Cantor’s collection spans 5,000 years and includes more than 38,000 works of art. Ranging from classical antiquities to contemporary works, the Cantor’s holdings include the largest collection of sculptures by renowned master Auguste Rodin in an American museum. With 24 galleries and more than 15 special exhibitions each year, the Cantor is one of the most visited university art museums in the country and is an established resource for teaching and research on campus. Free admission, tours, lectures, and family activities help the museum attract visitors from Stanford’s academic community, the San Francisco Bay Area, and from around the world.