Students of Fiction Experience Wright Morris’s Work On and Off the Page

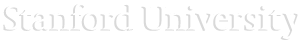

Last October, lecturer Sara Houghteling accompanied her six students to meet with Maggie Dethloff—then the Capital Group Foundation curatorial fellow for photography, now the Cantor’s assistant curator of photography and new media—and explore the Cantor’s trove of original images by Wright Morris. Houghteling’s Photography in Fiction course (English 182E) looks at fiction writers like Morris who transcend the boundary between the written word and other art forms. An American novelist, short-story writer, essayist, and photographer, Morris pioneered “photo-texts,” books in which he paired his photographs with his own writing.

What was it like to view these images outside the classroom?

When you enter the Cantor, especially a study room like the Wilsey, the rest of the world falls away. You can be completely in the moment, examining the physical object in front of you. Maggie had arrayed the original images along the wall so we could peer at them closely from different angles.

His photographs are absent any people, yet seem somewhat haunted.

At the start of our visit, Maggie presented a terrific lecture on Morris, establishing him within the context of his contemporaries—the most immediate comparison being Walker Evans—and defining Morris’s differences—say, a sense of intimacy rather than intrusiveness. We learned about Morris’s photographic production process and his use of the Rolleiflex camera, which is held at waist height and has a large view finder. But beyond that, she spoke about Morris’s personal life, how the early loss of his mother shaped his work. She died six days after his birth, and he often seems to be searching for her presence among the worn objects in the lived-in rooms he photographs.

Do you recall anything else that made this experience memorable?

Beyond the rare pleasure of seeing original Wright Morris images up close, Maggie—along with Class Visit and Tour Coordinator Kwang-Mi Ro and Director of Academic and Public Programs Peter Tokofsky—escorted us into the museum through the staff entrance. We certainly felt like honored guests entering a special place.

How did the visit expand your students’ perspectives?

You could perceive where his hand was in his artistic process. For class, we read his early novel The Home Place, from 1948. Because the Cantor has many of [the book’s] original images, we could scrutinize them closely. For example, in Drawer with Silverware, one student noticed that in Morris’s original at the Cantor, the date on the newspaper lining the drawer is visible. In the version Morris selects for his novel, he crops off the date. What? Why? We talked about how this adds to a sense of timelessness or announces the concept of a single time stamp as simplistic or mundane. It’s not part of his artistic project. I think it gave all of us the chills, to almost discern Morris’s presence in the room, in the photographs, and in the books, and to discover the choices he made based on his aesthetic aims and literary and even philosophical ideals.