Cantor Arts Center

328 Lomita Drive at Museum Way

Stanford, CA 94305-5060

Phone: 650-723-4177

SUSAN DACKERMAN, John and Jill Freidenrich Director, Cantor Arts Center

Although the museum established by Leland Sr. and Jane Stanford in memory of their son, Leland Jr., is celebrating its 125th anniversary this year, it has only been in active operation for a portion of that time. In the wake of the fifteen-year-old’s tragic death, his parents founded both Leland Stanford Junior University and the Leland Stanford Junior Museum, the latter of which opened in 1894 and was expanded in 1900. When it was built, its grandeur and scale were rivaled only by its East Coast contemporaries—the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Twelve years into its life, however, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake catastrophically toppled the majestic museum, and much of its collection was lost to the collapse and the looting that followed. Because Jane Stanford, the museum’s most vocal advocate, died in 1905, when it reopened in 1909 only a quarter of the former building was salvaged, and part of that space was given over to classrooms, laboratories, and storage rather than display. In 1945 the building closed for further renovations and did not reopen again until 1954. During this time a much-needed inventory of the art collection was conducted, and much was determined to be lost.

During that half century of the museum’s closure and instability, most other art museums across the nation were building their collections and developing their educational missions. Thus, from the 1950s through the 1980s, Stanford’s museum curators and art history faculty made up for lost time, heroically working to revitalize the institution into a worthy center for exhibitions, research, and teaching. But while lightning never strikes twice, earthquakes do, and in 1989 the Loma Prieta quake again critically damaged the building and its collections. The museum’s first century of existence was steeped in sorrow and destruction.

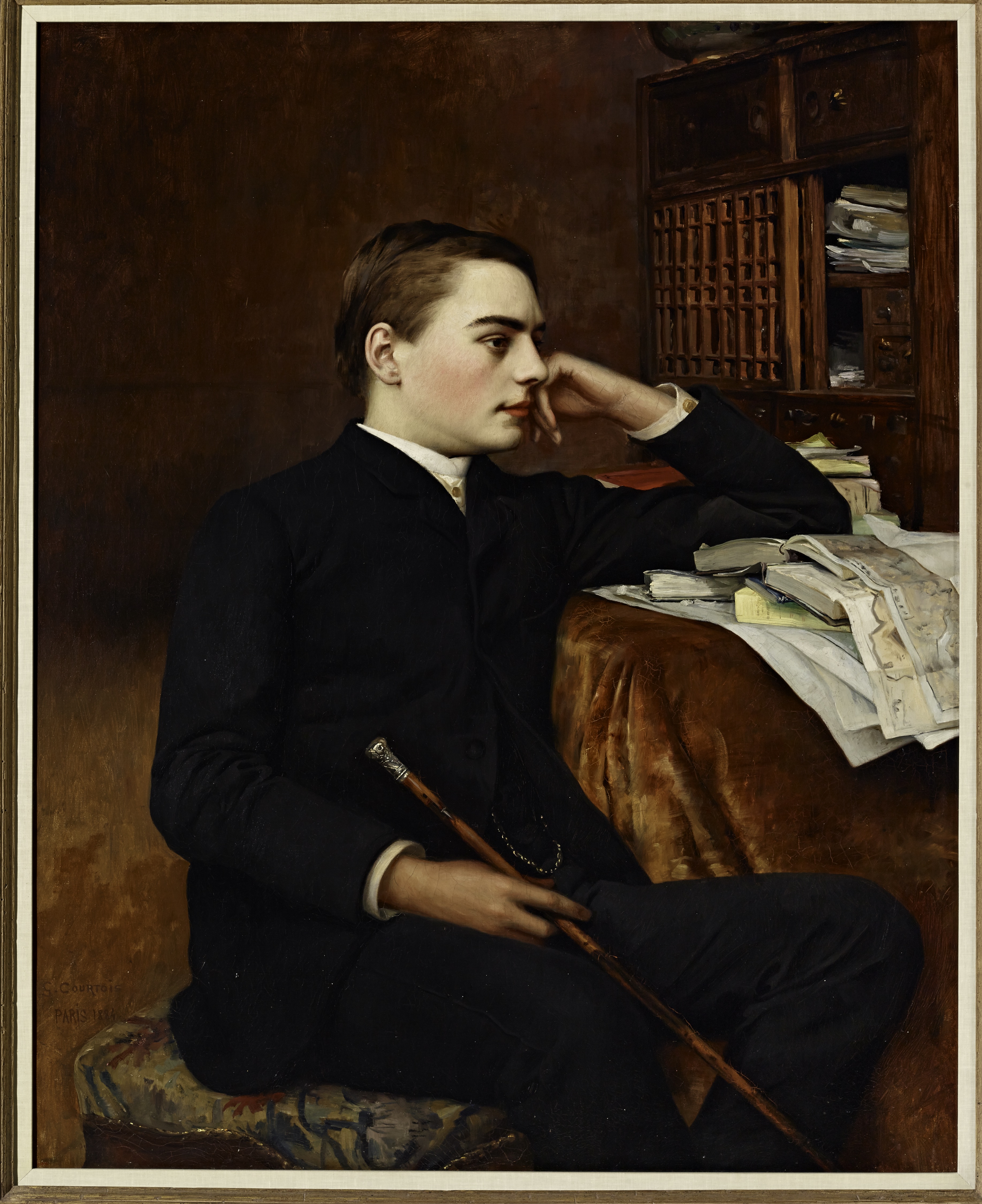

When the renamed Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts reopened in 1999, with a new addition on its southwest quadrant, it included galleries dedicated to the display of objects from the Stanford family’s original collection. The Stanfords’ idea to found a museum had emerged from their son’s capacious collecting and museological inclinations. At home he collected and displayed toys, Native American mortars and pestles, photographs, and taxidermied birds and animals, to which he added Egyptian and Mediterranean antiquities, relics of warfare, and other artistic and natural curiosities from his European travels. After the boy’s death in Florence in 1884, his parents continued to supplement his collection with objects from around the world—as he would have done himself had he lived. Born of love and grief, the collection kept their son’s dream of a museum, as well as his acquisitive nature, alive.

What happens when a museum is erected to contain all that love and sorrow? Although Leland Jr.’s death precipitated the founding of one of the most illustrious universities in the world, which in turn prompted the emergence of Silicon Valley and globe-changing technological innovations, his art museum continues to be the site of his mourning. While the proximate Stanford Mausoleum holds the eternal remains of father, mother, and son, their ghosts inhabit the museum. These apparitions take the form of memorial paintings, mundane objects that Leland Jr. and his parents gathered and held in their hands, goods of the indigenous people who originally populated the region, mementos of the Chinese workers who labored for the Stanfords, as well as artifacts of the family’s businesses, their Palo Alto home, and their deaths. How can a museum present a collection that embodies so much history and emotion?

All that grief, love, and mourning have found a new home in The Melancholy Museum, an installation created by artist Mark Dion. To house the objects Leland Jr. amassed, and the stuff his parents accumulated to remember him, Dion has created a mourning cabinet. The grand Victorian case houses the boy collector’s earthly and otherworldly sepulchral goods as well as his parents’ heartache, anguish, and hope. Through the past year, Dion has sorted through the remains of the Stanfords’ lives and dreams. He has examined with his own collector’s eye young Leland Jr.’s collection and identified those materials that best tell his and his museum’s story. Assembled on the cabinet’s shelves and drawers, the stuff narrates the boy’s life and death through images and objects related to the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water—and ether, his final resting place. Individually and collectively these aggregated materials give Leland Jr. and his parents an afterlife within the museum.

Dion also has excavated other Stanford histories, of both family and place. Digging through Special Collections and the Archaeology Center, he found assorted letters, ledgers, and objects to describe the lives and deaths of others whose lives and labor made possible the university and the museum and its collections. These causalities and tragedies are also represented in The Melancholy Museum in the form of fragmented pots, tools, and bodies.

Through objects alone, Dion’s installation tells the story of how one family’s rush West to sell hardware to prospectors resulted in the accumulation of vast wealth and power. The furniture, photographs, Native American objects, menus, and other artifacts of material life at the turn of the twentieth century that comprise the artwork show how the family upgraded its business interests to politics, the railroad, and a horse farm, and how those interests were enabled by land previously inhabited by the Ohlone people and the labor of Chinese and other immigrants. Finally, the grand Victorian mourning cabinet, the heart of Dion’s work, demonstrates how one teenage boy’s death resulted not in the creation of the nation’s largest museum but in a museum where love, grief, and mourning are forever entwined, The Melancholy Museum.