Cantor Arts Center

328 Lomita Drive at Museum Way

Stanford, CA 94305-5060

Phone: 650-723-4177

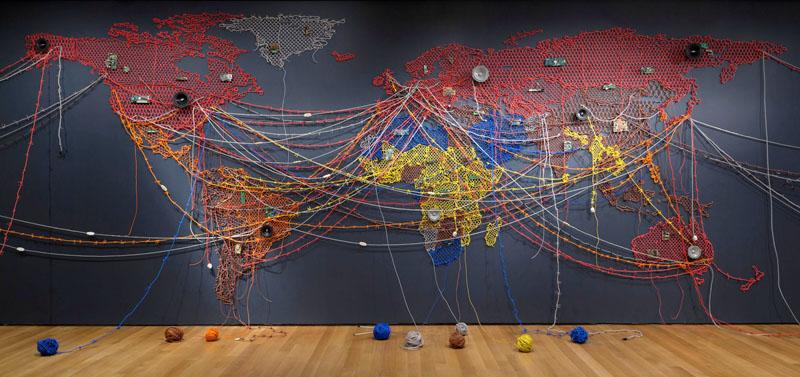

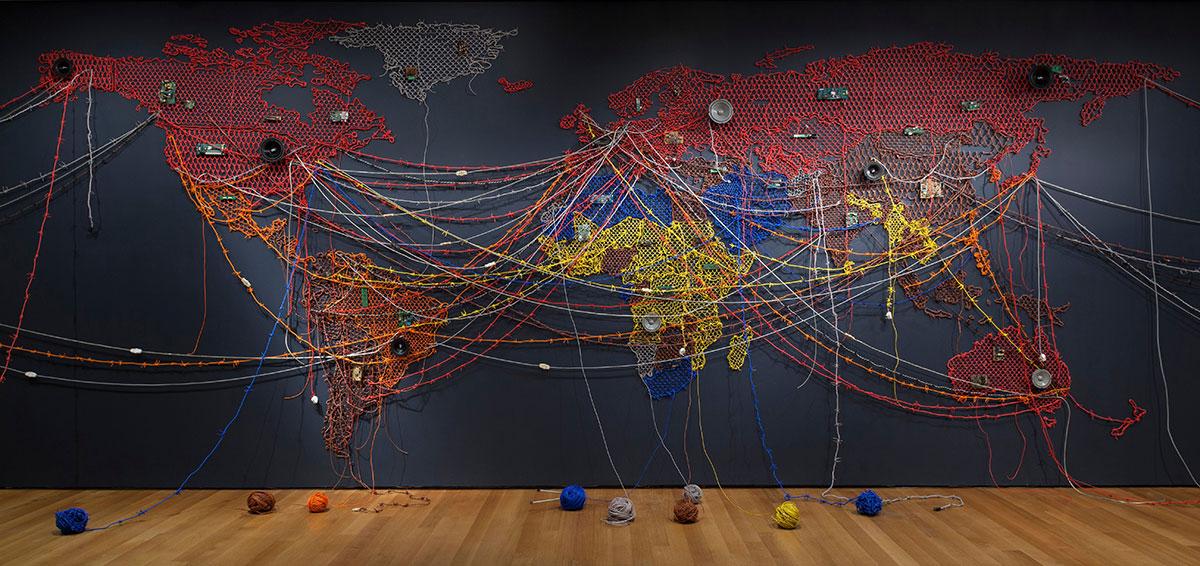

Reena Saini Kallat (India, b. 1973), Woven Chronicle, 2011–16. Circuit boards, speakers, electrical wires, and fittings; single‑channel audio (10:00 minutes); approximately 11 x 38 ft. © Reena Saini Kallat. Courtesy the artist and Nature Morte, New Delhi. Installation view, Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2016–17. Photograph by Jonathan Muzikar. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Migration—the movement of people and cultures—is a story of who we are and how we got here over time. Millions of people move for myriad reasons, from fleeing war and religious persecution to seeking better education or financial security. The United Nations estimates that one out of every seven people in the world is an international or internal migrant who moves by choice or by force. In this era of mass migration, and amid ongoing debates about it, When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art considers how contemporary artists respond to the migration and displacement of people worldwide. The exhibition borrows its title from a poem by Warsan Shire, a Somali-British poet who gives voice to the experiences of refugees. Through artworks made since 2000 by artists born in more than a dozen countries, this exhibition offers diverse artistic responses to migration, ranging from personal accounts to poetic meditations.

The Cantor Art Center’s presentation of When Home Won’t Let You Stay has particular resonance with the histories of displacement, migration, and immigration shaping California and the Bay Area. the bay Area is sited on the ancestral land of the Muwekma Ohlone people, who were forcefully displaced by Spanish-Mexican settlers and the westward expansion of the United States. This region is further defined as a major site of entry for immigrants from China, Japan, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, Mexico, and other Asian and Latin American countires. From the Gold Rush and the building of the transcontinental railroad to the state's agricultural boom, California has offered economic opportunity for both immigrants and internal migrants. Silicon valley's tech industry has continued to attract and employ people from all over the world, contributing to California's status as the most common destination for new immigrants to the United States.

Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, temporary border closures and restrictions on travel are impacting migrants, immigrants, and refugees in dire ways. The closure of the University and mandates to shelter in place have resulted in dislocation and even homelessness for students, as well as unprecedented shifts in everyone's relationship to home. By considering place and movement together, historically and in the present moment, When Home Won’t Let You Stay presents migration as a transformative force that continues to shape our region, our nation, and our world.

The exhibition is organized by Ruth Erickson, Mannion Family Curator, and Eva Respini, Barbara Lee Chief Curator, with Anni Pullagura, Curatorial Assistant, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston.

The Cantor Arts Center presentation is organized by Maggie Dethloff, Assistant Curator of Photography and New Media, and Jessica Ventura, Curatorial Assistant.

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Halperin Exhibition Fund.

Click on the images below to move through the galleries that are part of this exhibition. Within each section you'll find bonus content, opportunities to join the conversation by submitting answers to specific questions around the exhibition themes, as well as commentary from our Student Guides and Docents.

To get back to the exhibition page, simply click the back button of your browser. You will be redirected to the top of this page.

The Cantor’s presentation of When Home Won’t Let You Stay includes work by two additional artists, Golnar Adili and Diana Li, not included in the show’s previous iterations. Adili and Li both utilize found materials and evoke intergenerational memories of migration in their visual meditations on home and transit. Their artworks tell stories of particular interest to the Bay Area, where Asian American, Latin American, and Iranian American individuals have long been integral to the history and economy of Silicon Valley.

Woven Chronicle is a cartographic wall drawing that, in the artist’s words, represents “the global flows and movements of travelers, migrants, and labor.” Kallat uses electrical wires—some of which are twisted to resemble barbed wire—to create the lines, which are based on her meticulous research of transnational flows. Wire is an evocative and contradictory material: it operates as both a conduit of electricity, used to connect people across vast distances, and as a weaponized obstacle, such as the fences used to erect borders and encircle refugee camps. Kallat’s family was splintered by the Partition of India in 1947 upon independence from Britain, which divided the country geographically along religious lines and induced the movement of more than ten million people in one of the largest forced migrations in human history. Woven Chronicle speaks to this personal memory—and collective history—in its material presence, merging the artist’s research on migration with metaphors of violence, and accompanied by an ambient soundscape that evokes the steady hum of global movement.

Reena Saini Kallat (India, b. 1973), Woven Chronicle, 2011–19. Circuit boards, speakers, electrical wires, and fittings; single‑channel audio; approximately 11 x 38 ft. © Reena Saini Kallat. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Installation view, “Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter”, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 1, 2016–January 22, 2017. Photograph by Jonathan Muzikar. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

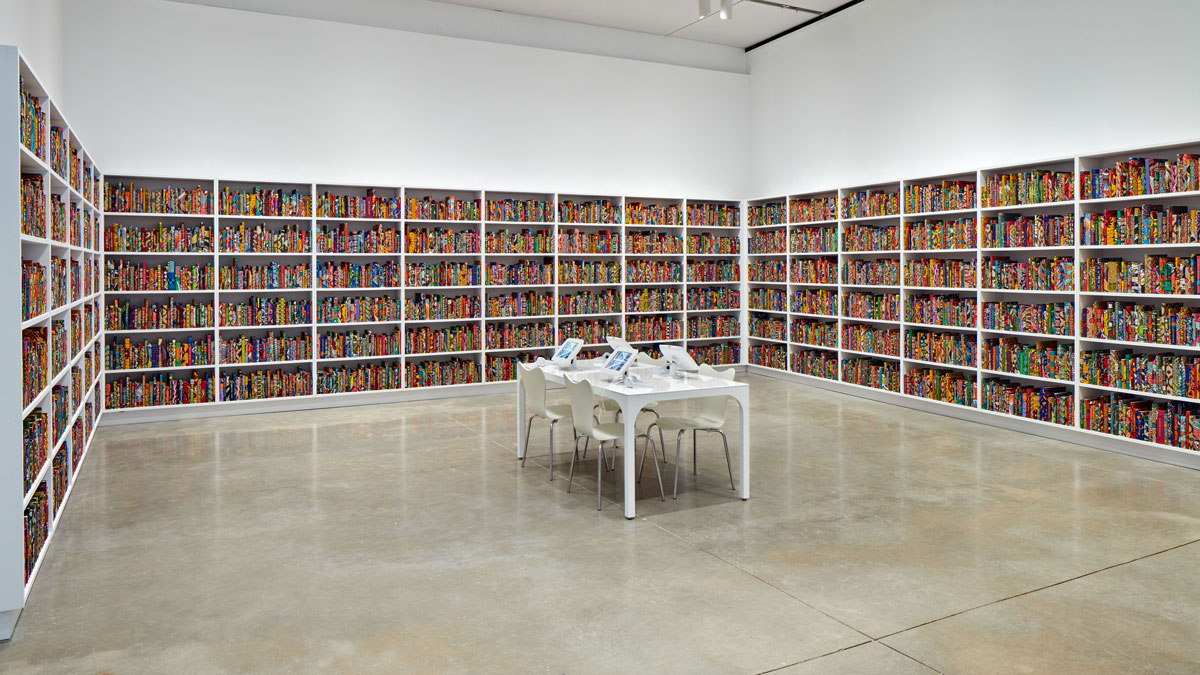

The American Library consists of six thousand volumes wrapped in vibrantly colored Dutch wax-print fabric. Many are embossed with the names of first- and second-generation immigrants or their descendants, or those affected by the Great Migration in the United States. All those named have made a mark on American culture: they include writers ranging from W. E. B. Du Bois to Grace Lee Boggs, Toni Morrison, and Teju Cole; artists such as Ana Mendieta; and industrialists such as Apple innovator Steve Jobs. These individuals span race, gender, and class, recasting how ideas of otherness, citizenship, home, and nationalism acquire their complex meanings. The fabric also reflects the complex interactions among cultures: introduced to West Africa in the nineteenth century through English and Dutch colonial trade as a mill-printed derivative of patterned batik cloth from Indonesia, the fabric has become synonymous with West African fashion and a key material for Yinka Shonibare CBE, RA, who was born in London and raised in Lagos, Nigeria. The American Library is an imaginative projection of a nation whose commonly told origin story is one of immigration.

Yinka Shonibare CBE (England, b. 1962), The American Library, 2018. Hardback books, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, gold foiled names, and website; dimensions variable. © Yinka Shonibare CBE. Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Installation view, “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art”, The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, October 23, 2019–January 26, 2020. Photograph by Charles Mayer

The Strait of Gibraltar is a highly surveilled waterway between Spain and Gibraltar to the north and the Moroccan port cities Ceuta and Tangier to the south; it is also the narrowest distance between Africa and Europe (approximately 8.9 miles, or 14.3 km, at its narrowest). As the point where the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea meet, the region has long been a highly contested political arena for the movement of people. Today, Tangier maintains a large population of migrants who are held in limbo as they await passage, whether to Europe, or elsewhere. Yto Barrada began the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project in 1998 to witness the tension between the Strait of Gibraltar’s allegorical nature and harsh reality. For Barrada, the work also carries a personal meditation on class and nationality. As a French and Moroccan citizen, she is free to cross the border while thousands are not. “In my images I no doubt exorcise the violence of departure, but I give myself up to the violence of return,” says Barrada. “The estrangement is that of a false familiarity.”

Slideshow Images:

Yto Barrada (France, b. 1971), Panneau—Publicité de lotissement touristique—Briech 2002 [Hoarding—advertising for a tourist development—Briech 2002], 2002. From the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project, 1998–2003. Chromogenic color print, 31-1/2 x 31-1/2 in. © Yto Barrada. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris. Courtesy Pace Gallery; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Yto Barrada (France, b. 1971), Rue de la Liberté, Tanger 2000, 2000. From the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project, 1998–2003. Chromogenic color print, 49-3/16 x 49-3/16 in. © Yto Barrada. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris. Courtesy Pace Gallery; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Yto Barrada (France, b. 1971), Le Détroit de Gibraltar—Reproduction d’une photographie aerienne—Tanger 2003 [The Strait of Gibraltar—reproduction of an aerial photograph—Tangier 2003], 2003. From the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project, 1998–2003. Chromogenic color print, 23-5/8 × 23-5/8 in. © Yto Barrada. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris. Courtesy Pace Gallery; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Yto Barrada (France, b. 1971), Salon de première—Ferry de Tanger à Algesiras, Espagne—2002 [First class lounge—Ferry from Tangier to Algeciras, Spain—2002], 2002. From the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project, 1998–2003. Chromogenic color print, 33 x 33 in. © Yto Barrada. Private collection, New York. Courtesy Pace Gallery; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Yto Barrada (France, b. 1971), Usine 1—Conditionnement de crevettes dans la zone franche, Tanger 1998 [Factory 1—Prawn Processing Plant in the Free Trade Zone, Tangier 1998], 1998. From the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project, 1998–2003. Chromogenic color print, 40-9/16 x 40-9/16 in. © Yto Barrada. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris. Courtesy Pace Gallery; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Yto Barrada (France, b. 1971), Arbre généalogique [Family Tree], 2005. Chromogenic color print, 59 x 59 in. © Yto Barrada. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris. Courtesy Pace Gallery; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg, Beirut; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

“I consider migration to be a process,” says Do Ho Suh “not something that happens overnight. Each step of the process is like crossing another threshold.” Impressions of space, environment, and home are central to Suh’s art, which explores a poetic language for memory through materials and architecture. His fabric sculptures depict rooms, thresholds, and passageways from the artist’s former living spaces constructed with diaphanous polyester, whose translucency evokes the nature of memory. They are painstakingly sewn in one-to-one scale, with doorknobs, molding, and outlets crafted in precise detail. The works shown here represent two spaces from the artist’s childhood home in South Korea: the entry and eating area. He imaginatively links places he has lived, reconfiguring memories of home in the present.

Do Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962), Hub-1, Entrance, 260-7, Sungbook-Dong, Sungboo-Ku, Seoul, Korea, 2018. Polyester fabric and stainless steel, 97-3/16 x 150-1/4 x 132-5/8 in. © Do Ho Suh. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul

Do Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962), Hub-2, Breakfast Corner, 260-7, Sungbook-Dong, Sungboo-Ku, Seoul, Korea, 2018. Polyester fabric and stainless steel, 106-5/8 × 140-9/16 × 128-7/16 in. © Do Ho Suh. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul

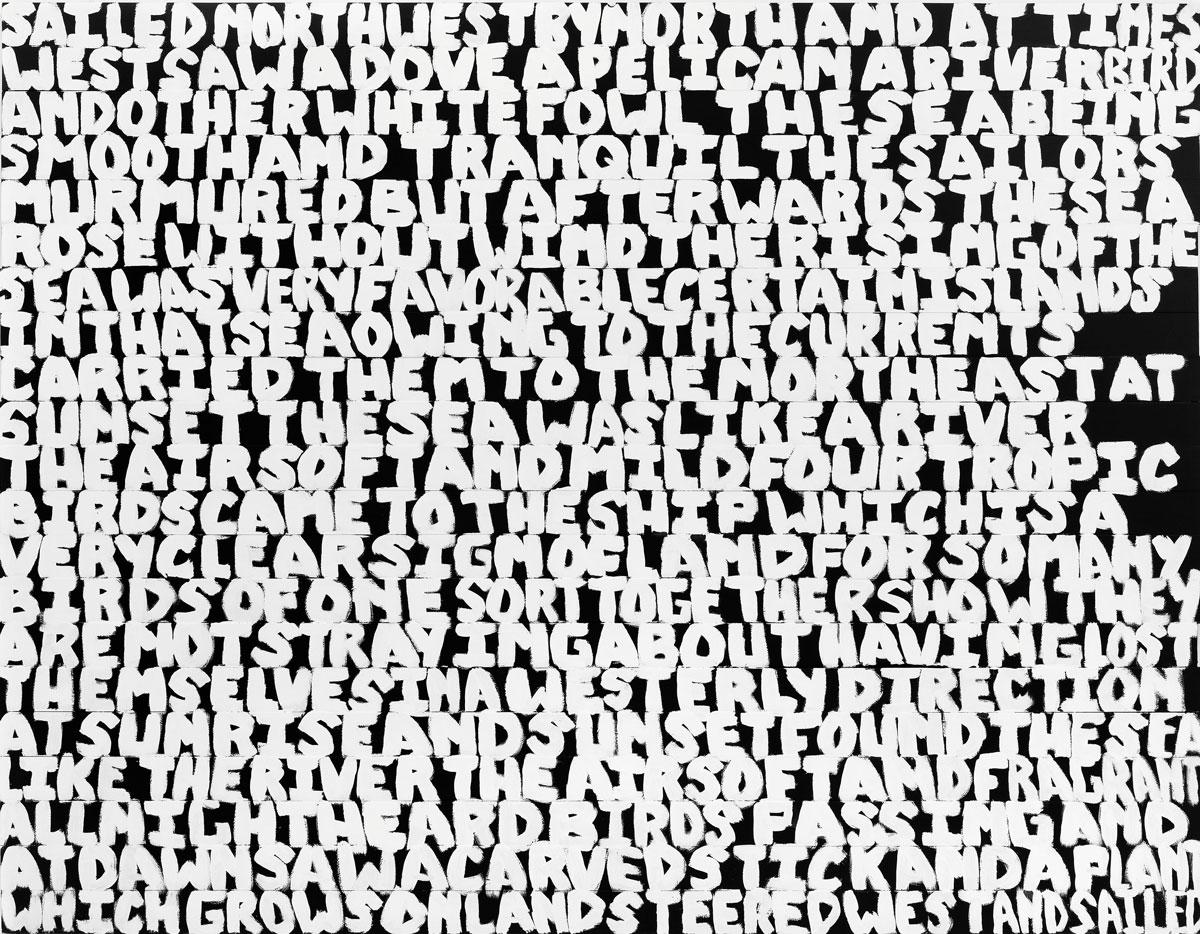

One of several text paintings in the series Sundown, Found the Sea Like the River features excerpts from Christopher Columbus’s diaries, hand-lettered by the artist as a reconfigured text. Placing his pastoral meditation on landscape in marked contrast with the colonial violence that characterized this era of encounter, Simmons brings history into the present. She does not quote verbatim but rather, in her words, “sculpts from the language,” focusing on Columbus’s encounters with landscape rather than people. Columbus’s writings reveal a colonial action of undoing and fragmentation in the violent and intentional erasure of First Nations’ cultures and peoples. This is echoed in Simmons’s textual and visual juxtapositions, which reconstruct the personal narrative as poetry, and render the intimate contents of the diary in the scale of public signage. In its size and style, the painting’s declarative and urgent quality eclipses Columbus’s expressions of marvel and relief at his newfound environment, creating a textual image that, in Simmons’s words, “is idyllic yet loaded with historical conflict.”

Xaviera Simmons (U.S.A., b. 1974), Found the Sea Like the River, 2018. Acrylic on wood panel, 72 x 96 in. © Xaviera Simmons. Courtesy the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Miami

In this animation, Stanford student and Cantor Student Guide Sadie Blancaflor reads the cramped text in Found the Sea Like the River and translates it into visual imagery.