A Personal Mediation on When Home Won’t Let You Stay

By Shaquille Heath

Growing up, we were quite poor, and by the time I was 12 years old I had lived in 10 different houses. One of our longer stays was a home that I aptly named the “yellow” house. The yellow house had a small hallway, with a white cabinet that held a chest of drawers built right into the wall. I was a restless child and once out of boredom, I had scavenged the cabinet for something of interest when I realized that you could jimmy the back wall open to unearth a wonderful little nook. I decided to make this discovery my hiding place, where I would stow my most precious items for long-term safekeeping. I imagined that in 20 years I could come back to the yellow house and would politely ask to be shown to the cabinet, where I could reopen the nook and find my treasures waiting for me; and I could bring them to an actual home that would be ours completely, and we would not have to move again – if we did not want to. Years later, driving past the yellow house’s street, I was startled to find that the building had been replaced with a large empty lot. Due to the house’s unfitness, the home had been condemned and demolished, and with it, my treasures too.

I’m not sure that there is a specific age when we begin to realize what “home” is, but I feel assured that it is younger than we can fathom. Its presence marks us. We begin to wonder, is home a safe place that holds our dearest treasures? Is it where our family and loved ones are? When is it material? And when is it intangible? Is it ours, even when it disappears from our sight?

These questions are at the heart of When Home Won’t Let You Stay (WHWLYS), on view at the Cantor Arts Center through May 30, 2021. In more than 40 pieces, WHWLYS forces us to consider our complicated relationship to the subject, through the powerful stories of those who migrate. Eighteen artists from a dozen different countries compel us to reflect upon the privilege of home, through varied artistic responses to the experiences of refugees, immigrants and migrants. I realize that their reflections are far more pressing than the tale of my yellow house, but the considerations remain related. We all have an intricate story for what we define as “home,” and the answer influences and shapes our endless search for identity and belonging.

“The show includes all kinds of media. We've got installation, video works, painting, photography and sculpture,” notes Maggie Dethloff, assistant curator of photography and new media, and the curator of the exhibition’s presentation at the Cantor. “The pieces range in how they engage with migration as a topic. There are some artists who are migrants or refugees themselves, and so they’re speaking from a more personal perspective. While other artists work as photo documentarians, or in poetic modes. So you get a really wide range of reflections and ideas of home.” WHWLYS is one of the largest sized shows to be on view at the Cantor, installed throughout the museum, from galleries, to the lobby, the Cantor’s balcony and even in hallways. Dethloff notes, “The fact that one has to sort of migrate through the museum in order to see the whole show is definitely something unique.”

As you enter the museum, the first work installed in the foyer is that of Tania Brugera. Suspended from the Cantor’s ceiling, the piece itself presents a bright-blue flag, stitched with a Pangea-like map and emblazoned with the words Dignity Has No Nationality, (which also serves as the name of the work from 2017.) Brugera is the founder of the Queens-based project Immigrant Movement International, an artist initiative that works to empower local transnational and undocumented residents and families. By reverting the Earth’s map back to that of Pangea, Brugera returns us to a world before borders. Without nationality or citizenship, the work prompts us to dream of a future that affirms our fundamental shared humanity. Dignity Has No Nationality becomes a beacon, the quintessential mind frame for engaging with the rest of the show.

On the second floor of the museum works from Aliza Nisenbaum, reflecting on Mexican immigration to the U.S., Adrian Piper on how institutions, such as the US Transportation Security Administration, impact feelings of attachment to home, and Xaviera Simmons on Columbus’s “discovery” of America, share a wall that embodies different perspectives on America as “home.”

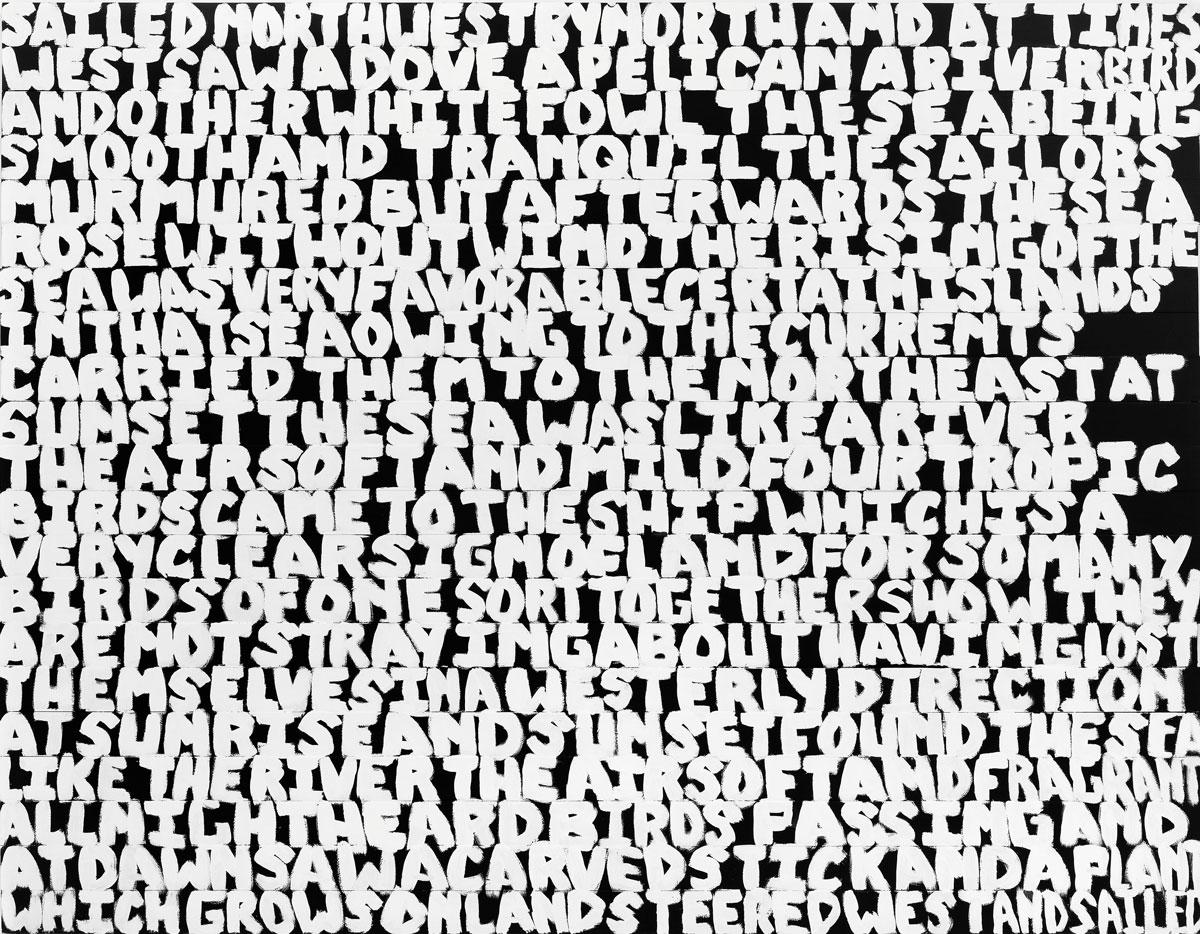

Simmons’ Found the Sea Like the River, 2018, features large wooden planks painted black and inscribed with excerpts from Christopher Columbus’s diaries during his travels to America. In bold white letters, the writing includes words such as “tranquil” and “soft,” cramped into the canvas. Reading Columbus's romanticized text was agonizing. In this, Simmons forces us to contend with the whitewashed narratives many of us learned growing up in regard to Columbus’s horrific slaughter and enslavement of indigenous communities. Yet, wasn’t it only just this past summer, after the murder of George Floyd, that cities began to question and remove Columbus statues from public spaces?

Sadie Blancaflor is a junior at Stanford, majoring in Earth systems and anthropology, and serves as a student guide for the exhibition’s virtual tour, sharing thoughts specifically about Simmons’s piece. “This exhibit, as a whole, is an attempt to really dig into and rewrite history, and to portray it in the way in which it has historically impacted communities,” Blancaflor noted. “Simmons does a really powerful job of digging into that. Not necessarily rewriting because she is taking Columbus's actual words.” Blancaflor, whose studies center around displacement in relation to climate change, closes her video with a powerful question: “What do you think happens when the true narratives of discovery and homecoming are destroyed in the writings of history?”

From San Mateo, California, Diana Li’s work Nest, 2015, hangs inside the Ruth Levison Halperin gallery. The piece is constructed of electrical wires collected from her parents’ backyard, the remnants of her father’s work as an electrician. Woven together, Li creates a structure that physically embodies a nest, while also figuratively reflects on the idea of nests as temporary structures of home.

“I was thinking a lot about Asian American representation, because there were a couple films that came out, where Matt Damon was in The Great Wall and Scarlett Johansson in Ghost in the Shell,” shared Li about films with white actors in Asian roles. ”And I was reflecting on that and how it connected to my dad's work as a technician, while living in the Bay Area as a tech hub.”

Nest is a piece that also explores the invisibility of labor, observed firsthand through watching her father work. “I grew up going to jobs with my dad and going to clients' homes. A lot of these families are middle class to rich upper-class families living in the heart of Silicon Valley,” noted Li. “When I was making that piece, I was thinking a lot about how our home is in service of other homes in the Bay Area … and I thought about how we want to invisibilize these cables and invisibilize the labor involved. And so we hide them behind these walls, wood, cement.”

Li shared her own personal experience of watching her home change over the years because of the tech industry. “A lot of the homes in my neighborhood are turning from homes into condos and so each lot has multiple homes that people could live in. We're seeing the change all around us, literally, outside the front door.” Li, who lives in Oakland now, works for the Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center, as well as the Asian American Women Artists Association. “Being able to call this my home is definitely a privilege. And also an honor to be able to serve my community, and where I grew up, too.”

Each work in WHWLYS is personal, distinctive in location, perspective and medium, yet their roots expose an interconnection. What scars are produced when home is stolen from us? What are our considerations of “home” when it is forced upon us? And at the heart of it all, is it still a choice when “home” won’t let you stay?

In my conversation with Dethloff, I was curious how thoughts of home had changed for her through working with the exhibition. She said, “My focus in the exhibition has changed over time as I've been working on it because it started with a really kind of heavy focus on these histories of migration and immigration. But these questions of home are so deeply embedded.” If home is where the heart is, WHWLYS confirms the notion that it’s something we carry with us, for better or for worse.