By Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, PhD.

Assistant Curator of American Art, Cantor Arts Center

Throughout the history of American art, portrait paintings have been used as a means to many ends: to memorialize those who have passed, to teach future generations about important historical figures, and to sanctify legacies. As viewers, we gaze at these captured likenesses presented on the walls of museums and reproduced in textbooks with the tacit acceptance, more often than not, that these sitters are worthy subjects of art. But who decides who is worthy of a painting, and what constitutes worthiness in artistic representation?

As a young person, I accepted these painted representations of historical American figures without question and never thought about the types of faces I wasn’t seeing. Gustave Courtois’s 1884 portrait of Leland Stanford Jr. is a prime example of grand European and American portraiture of the time period and a foundational object in the Cantor’s collection. Everything about this image of a young Leland Jr. communicates affluence and power, from his refined yet understated garb to a setting that reveals his scholarly interests. Through amassing and inheriting wealth, elite figures, like the Stanfords, could and did amass representations of themselves. An object like a portrait is very often an expression of social and economic capital. Can we separate the history of visual representation from the history of wealth in this country?

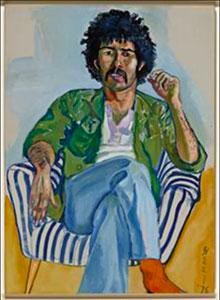

In my early days of art historical study, I rarely, if ever, saw works of art featuring human figures who resembled myself or my mother. It took years of research at the graduate level to find the types of images I was interested in seeing—ones that honored and revealed a more truthful representation of our nation’s population. Contemporary artists like Alice Neel, Titus Kaphar, and Jordan Casteel—whose first solo museum exhibition was mounted at the Cantor in fall 2019—all showcase a wide range of sitters in their portraits. Beyond highlighting diversity, their paintings complicate, challenge, and broaden our understanding of what constitutes worthiness in artistic representation and who gets to make decisions about worthiness in the first place.

When it comes to the matter of historical portraiture, we should ask and seek answers to such questions as who is being represented, and why? how are they represented? and is their representation mounted on the oppression of others?

Thankfully, we are in a moment when people, especially young people, are more attuned than ever to issues of representation in art, culture, and politics. They are asking museums to answer the aforementioned questions and be accountable for how they have marginalized nondominant narratives of American history. They are challenging the presence of public monuments that perpetuate inaccurate and harmful historical narratives. History will be better served by the awakened critical faculties of today’s youth. They understand, fundamentally, that Black lives matter. If this is the new normal, then I am all for it.

Curious for more? Explore in-depth art history object lessons from our curatorial staff by visiting our Learning Guides Page.