Cantor Arts Center

328 Lomita Drive at Museum Way

Stanford, CA 94305-5060

Phone: 650-723-4177

Migration—the movement of people and cultures—is a story of who we are and how we got here over time. Millions of people move for myriad reasons, from fleeing war and religious persecution to seeking better education or financial security. The United Nations estimates that one out of every seven people in the world is an international or internal migrant who moves by choice or by force. In this era of mass migration, and amid ongoing debates about it, When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art considers how contemporary artists respond to the migration and displacement of people worldwide. The exhibition borrows its title from a poem by Warsan Shire, a Somali-British poet who gives voice to the experiences of refugees. Through artworks made since 2000 by artists born in more than a dozen countries, this exhibition offers diverse artistic responses to migration, ranging from personal accounts to poetic meditations.

The Cantor Art Center’s presentation of When Home Won’t Let You Stay has particular resonance with the histories of displacement, migration, and immigration shaping California and the Bay Area. the bay Area is sited on the ancestral land of the Muwekma Ohlone people, who were forcefully displaced by Spanish-Mexican settlers and the westward expansion of the United States. This region is further defined as a major site of entry for immigrants from China, Japan, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, Mexico, and other Asian and Latin American countires. From the Gold Rush and the building of the transcontinental railroad to the state's agricultural boom, California has offered economic opportunity for both immigrants and internal migrants. Silicon valley's tech industry has continued to attract and employ people from all over the world, contributing to California's status as the most common destination for new immigrants to the United States.

Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, temporary border closures and restrictions on travel are impacting migrants, immigrants, and refugees in dire ways. The closure of the University and mandates to shelter in place have resulted in dislocation and even homelessness for students, as well as unprecedented shifts in everyone's relationship to home. By considering place and movement together, historically and in the present moment, When Home Won’t Let You Stay presents migration as a transformative force that continues to shape our region, our nation, and our world.

This exhibition is organized by Ruth Erickson, Mannion Family Curator, and Eva Respini, Barbara Lee Chief Curator, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston.

The Cantor Arts Center presentation is organized by Maggie Dethloff, Assistant Curator of Photography and New Media, and Jessica Ventura, Curatorial Assistant.

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Halperin Exhibition Fund.

No one leaves home

unless home is the mouth of a shark.

You only run for the border

when you see the whole city

running as well.

Your neighbours running faster than you,

the boy you went to school with

who kissed you dizzy behind

the old tin factory

is holding a gun bigger than his body,

you only leave home

when home won’t let you stay.

No one would leave home unless home

chased you, fire under feet,

hot blood in your belly.

It’s not something you ever thought about

doing, and so when you did—

you carried the anthem under your breath,

waiting until the airport toilet

to tear up the passport and swallow—

each mouthful making it clear that

you would not be going back.

You must understand,

no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land.

Who would choose days and nights

in the stomach of a truck,

unless the miles travelled

meant something more than journey.

No one would choose to crawl under fences,

be beaten until your shadow leaves you

raped, then drowned, forced to the bottom of

a boat because you are darker, be sold,

starved, shot at the border like a sick animal,

be pitied, lose your name, lose your family,

make a refugee camp a home for a year or two or ten

stripped and searched, find prison everywhere

and if you survive

and you are greeted on the other side

go home blacks, refugees

dirty immigrants, asylum seekers

sucking our country dry of milk,

dark, with their hands out

smell strange, savage—

look what they’ve done to their own countries,

what will they do to ours?

The dirty looks in the street

feel softer than a limb torn off,

the indignity of everyday life more tender

than fourteen men who look like your father,

Between your legs. Insults easier to swallow

than rubble, than your child’s body

in pieces—for now, forget about pride

your survival is more important.

I want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

unless home tells you to

leave what you could not behind,

even if it’s human.

No one leaves home until home

is a damp voice in your ear saying

leave, run now, I don’t know what

I’ve become.

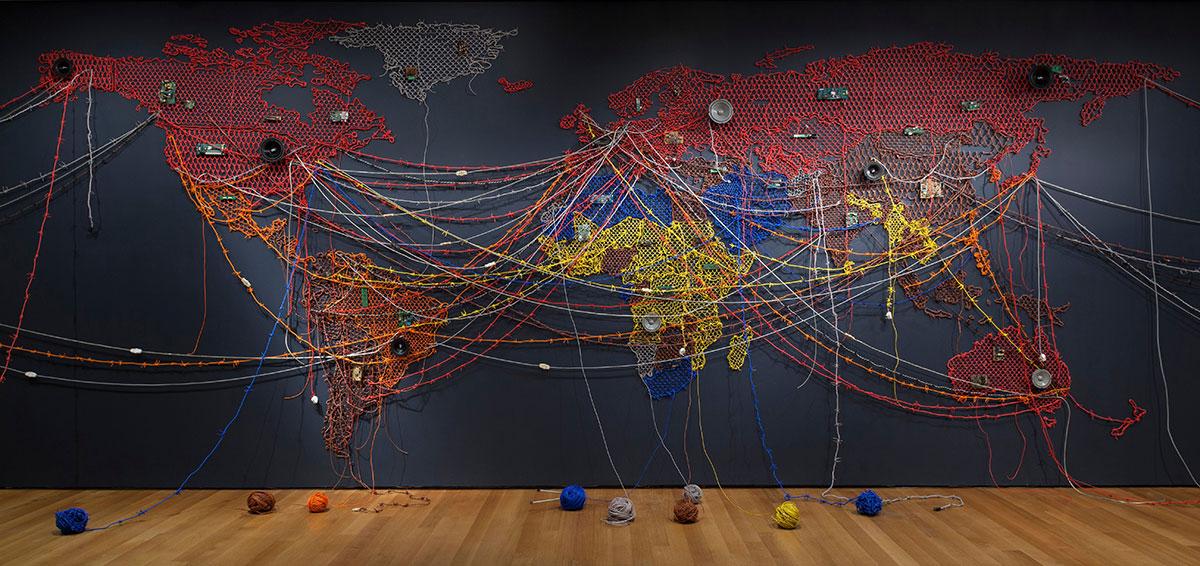

Electrical wires, speakers, circuit boards, and fittings; single-channel audio (sound; 10:00 minutes)

Courtesy Reena Kallat Studio and Nature Morte, New Delhi

Woven Chronicle is a cartographic wall drawing that, in the artist’s words, represents “the global flows and movements of travelers, migrants, and labor.” Kallat uses electrical wires—some of which are twisted to resemble barbed wire—to create the lines, which are based on her meticulous research of transnational flows. Wire is an evocative and contradictory material: it operates as both a conduit of electricity, used to connect people across vast distances, and as a weaponized obstacle, such as the fences used to erect borders and encircle refugee camps. Kallat’s family was splintered by the Partition of India in 1947 upon independence from Britain, which divided the country geographically along religious lines and induced the movement of more than ten million people in one of the largest forced migrations in human history. Woven Chronicle speaks to this personal memory—and collective history—in its material presence, merging the artist’s research on migration with metaphors of violence, and accompanied by an ambient soundscape that evokes the steady hum of global movement.

Electrical wires, speakers, circuit boards, and fittings; single-channel audio (sound; 10:00 minutes)

Courtesy Reena Kallat Studio and Nature Morte, New Delhi

Woven Chronicle is a cartographic wall drawing that, in the artist’s words, represents “the global flows and movements of travelers, migrants, and labor.” Kallat uses electrical wires—some of which are twisted to resemble barbed wire—to create the lines, which are based on her meticulous research of transnational flows. Wire is an evocative and contradictory material: it operates as both a conduit of electricity, used to connect people across vast distances, and as a weaponized obstacle, such as the fences used to erect borders and encircle refugee camps. Kallat’s family was splintered by the Partition of India in 1947 upon independence from Britain, which divided the country geographically along religious lines and induced the movement of more than ten million people in one of the largest forced migrations in human history. Woven Chronicle speaks to this personal memory—and collective history—in its material presence, merging the artist’s research on migration with metaphors of violence, and accompanied by an ambient soundscape that evokes the steady hum of global movement.

(Born 1971 in Paris, France; lives and works in Tangier, Morocco and New York, NY)

The Strait of Gibraltar is a highly surveilled waterway between Spain and Gibraltar to the north and the Moroccan port cities Ceuta and Tangier to the south; it is also the narrowest distance between Africa and Europe (approximately 8.9 miles, or 14.3 km, at its narrowest). As the point where the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea meet, the region has long been a highly contested political arena for the movement of people. Today, Tangier maintains a large population of migrants who are held in limbo as they await passage, whether to Europe, or elsewhere. Yto Barrada began the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project in 1998 to witness the tension between the Strait of Gibraltar’s allegorical nature and harsh reality. For Barrada, the work also carries a personal meditation on class and nationality. As a French and Moroccan citizen, she is free to cross the border while thousands are not. “In my images I no doubt exorcise the violence of departure, but I give myself up to the violence of return,” says Barrada. “The estrangement is that of a false familiarity.”

Slideshow Images:

Panneau—Publicité de lotissement touristique—Briech 2002 [Hoarding—advertising for a tourist development—Briech 2002], 2002

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Rue de la Liberté, Tanger 2000, 2000

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Le Détroit de Gibraltar—Reproduction d’une photographie aerienne—Tanger 2003 [The Strait of Gibraltar—reproduction of an aerial photograph—Tangier 2003], 2003

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Salon de première—Ferry de Tanger a Algésiras, Espagne—2002 [First class lounge—Ferry from Tangier to Algeciras, Spain—2002], 2002 Private collection

Usine 1—Conditionnement de crevettes dans la zone franche, Tanger 1998 [Factory 1—Prawn Processing Plant in the Free Trade Zone, Tangier 1998], 1998

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

From the series A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project, 1998–2003

Arbre généalogique [Family Tree], 2005

Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York

All chromogenic color prints

(Born 1962 in London, England; lives and works in London, England)

The American Library, 2018

Hardback books, Dutch wax-printed cotton textile, gold-foiled names, and website

Rennie Collection, Vancouver

The American Library consists of six thousand volumes wrapped in vibrantly colored Dutch wax-print fabric. Many are embossed with the names of first- and second-generation immigrants or their descendants, or those affected by the Great Migration in the United States. All those named have made a mark on American culture: they include writers ranging from W. E. B. Du Bois to Grace Lee Boggs, Toni Morrison, and Teju Cole; artists such as Ana Mendieta; and industrialists such as Apple innovator Steve Jobs. These individuals span race, gender, and class, recasting how ideas of otherness, citizenship, home, and nationalism acquire their complex meanings. The fabric also reflects the complex interactions among cultures: introduced to West Africa in the nineteenth century through English and Dutch colonial trade as a mill-printed derivative of patterned batik cloth from Indonesia, the fabric has become synonymous with West African fashion and a key material for Yinka Shonibare CBE, RA, who was born in London and raised in Lagos, Nigeria. The American Library is an imaginative projection of a nation whose commonly told origin story is one of immigration.